Baumbach: Marriage Story (2019)

Marriage Story is Noah Baumbach’s take on a certain strand of arthouse cinema that presents the decline of a New York romance, and the decline of a New York family, as the horizon of all gravitas and pathos. It’s the kind of cinema, from Woody Allen to Edward Burns, that is invested in the idea of cinema as heightened theatre, and committed to the New York cinema scene as symbiotically integrated with Broadway. Conversely, it’s the kind of cinema that tends to be sceptical of cinematic spectacle, and sceptical of Los Angeles as the epicentre of the cinema industry – a scepticism that is particularly evident in the third act of Annie Hall, when Woody Allen’s character, Alvy Singer, travels to Los Angeles to try and win Annie back. Nearly always, this brand of New York cinema valorises the husband, father and male auteur, which is perhaps why Baumbach chose it to reflect upon his own marriage, and the way the breakdown of his marriage relates to his career as a film director.

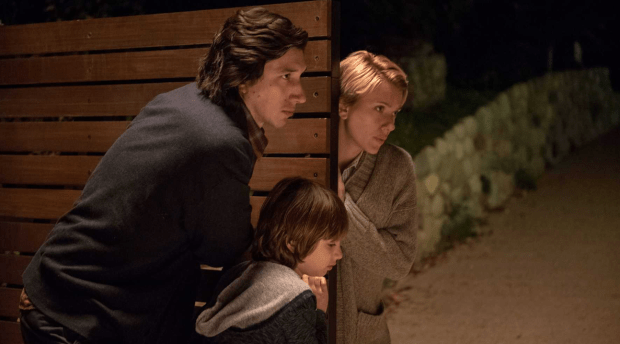

As with Woody Allen, Marriage Story starts off with a nod to Ingmar Bergman, as the two main characters, Charlie Barber (Adam Driver) and Nicole Barber (Scarlett Johansson), each deliver a monologue about their marriage in the style of Scenes From a Marriage. Like Baumbach’s film, which has only received a limited theatrical release before heading to Netflix, Bergman’s film also straddled the line between cinematic and televisual production, since it was first broadcast as a limited television series, and later condensed into a more conventional cinematic release. During these opening monologues, we learn that Nicole grew up in Los Angeles, where she was on the cusp of a successful film career before she moved to New York to marry Charlie and start a family. In New York, she sacrificed her film career to become an actor in his experimental theatre troupe. At the very moment at which Charlie is offered a Broadway fixture, however, Nicole decides that she wants a divorce, and that she wants to take their son Henry back to Los Angeles to resume her big screen career.

From these two monologues, it’s clear that Charlie is used to holding the power in his relationship with Nicole. Since she gave up her career in Los Angeles to become his muse, she has become an integral part of his theatre company, but not powerful enough for him to permit her to direct or conceive any productions of her own. As he puts it, “my crazy ideas are her favourite things to try and execute,” meaning that their relationship is based around him “giving her notes” on her performances, even in the midst of their most fraught arguments. Over time, their marriage has become an institution amongst their friends, and has been collapsed into his theatre company, with the result that Charlie can’t conceive of Nicole leaving him any more than he can conceive of not following his own interests, so thoroughly has he incorporated her artistic ambitions and career into his New York identity.

For all that Marriage Story has been publicized as a custody film, then, it’s really more about Charlie and Nicole’s professional lives, and the way professional ambitions can undercut an equitable marriage. Although Nicole’s screen career was peaking when she moved to New York, Charlie isn’t prepared to make the same sacrifice for her, citing his Broadway show and his receipt of a Macarthur Grant as a reason for remaining in New York. In reality, though, Charlie has never been prepared to spend any time in Los Angeles – we quickly learn that he turned down a six month Geffen residency, despite dragging Nicole and Henry to a residency in Copenhagen around the same time. Most of the film is thus driven by Charlie’s intractability about leaving New York, his inability to imagine himself without New York as a backdrop, and his refusal of even the most basic reciprocity of the gesture that Nicole originally made in leaving her career, family and home town to be a part of his world.

In that sense, Marriage Story is as much about the role that New York plays in Baumbach’s filmography, and in this particular kind of marriage drama, as it is about the specificities of Nicole and Charlie’s relationship. Charlie is so confident in his role as auteur that he has an affair with one of his theatre employees just for the sake of it, but this is never the main focus of the film, or the main motivation for the divorce, which is geographic and professional in nature, rather than bound up with sexual jealousy or infidelity. Much of the film follows Charlie as he tries to come to terms with Los Angeles as a diffuse space of imminent divorce, a place where he encounters Nicole as “the opposite of a fiancée,” detached from the strict professional hierarchy that structures their relationship in New York. Time and again, Charlie adopts poses and postures that don’t make sense in Los Angeles, most memorably when he is forced to spend a “second Halloween” with Henry after Nicole and her family take him for a “first Halloween” in Pasadena. While Nicole is attuned to the parts of Los Angeles, like Pasadena, that are conducive to trick-or-treating, Charlie spends the whole night driving around Sunset Boulevard and knocking on silent doors, before buying candy at a drive-in convenience store in lieu of a single successful trick-or-treat, all the while dressed up glumly as the Invisible Man from James Whale’s 1933 film.

The movement to Los Angeles thus gradually disenfranchises the insularity of the New York drama that Charlie wants to erect around his ambitions and aspirations – the same drama that Baumbach has riffed on for most of his career, culminating with the elegiac treatment of The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected). As a result, Marriage Story often plays like Baumbach’s summative meditation on the way that his auteurism has shaped his perception of himself, his career and his own relationships. At times, it’s hard not to situate that trajectory against Baumbach’s affair with Greta Gerwig and divorce from Jennifer Jason Leigh, especially since much of the dialogue feels ripped from real divorce proceedings. Where Charlie prohibits Nicole from directing any of the productions in his theatre company, Gerwig’s role as a director has really taken off in the wake of Lady Bird and Little Women. Between those two poles, and between the stories of Marriage Story and The Meyerowitz Stories, Baumbach often seems to be questioning his own outlook as much as Charlie’s, using Charlie to query the aspects of his auteurism he may have taken for granted.

This creates an odd and compelling rhythm whereby the film initially and instinctively aligns itself with Charlie, and Charlie’s delusions about himself, only to gradually and inexorably concede the limitations of Charlie’s worldview. In the opening scenes, we’re encouraged to identify with Charlie’s fairly condescending vision of Los Angeles, as Nicole’s family are presented in a waspy, slapstick register that effectively turns them into sidebars for Charlie himself, who they all love and adore. Since Charlie sees Nicole’s film career as a threat to his more theatrical aspirations, he tries to import the theatrical cues of New York art cinema to Los Angeles, and Baumbach follows suit, opting for simple colours, clean fabrics, long shots and hypnotic monologues that often recall Louis CK’s Horace and Pete. Despite occasional flashes of bright cityscape, most of the Los Angeles backdrops are so muted and monochromatic that they could easily be remade as stage backdrops, producing a kind of aesthetic of false naturalism, or false immediacy, that corresponds to Charlie’s ongoing desire to simply talk things through with Nicole in his apartment, in an unmediated manner.

Nicole proves just as resistant to this situation, continually dodging every effort that Charlie makes to initiate a “sincere” or “direct” or “transparent” discussion about their divorce. Her hesitations are well grounded, since we gradually learn that there is no space in their relationship that is not mediated through Charlie’s theatrical ambitions, which were first articulated to Nicole in precisely the “unmediated” space he invokes to her now, in the form of his Los Angeles apartment, as the best venue to enter into these conversations. In her discussion with her lawyer Nora Fanshaw, played by Laura Dern, Nicole recalls how she first saw Charlie in an experimental play that took place in his apartment. There was no stage, no seats, no distinction between actors and audience. Instead, the apartment was simultaneously both Charlie’s private domestic space and the venue for his experimental performance – a combination he has maintained ever since, and expected Nicole to maintain as well. Even when he settles into his apartment in Los Angeles, he keeps it bare, as if to reproach Nicole for not having the unmediated discussion he demands. In doing so, however, he simply sets out to recapitulate the theatrical performance that seduced her in the first place, before inducing her to sacrifice her career for his artistic and marital outlook.

No surprise, then, that when Nicole does finally agree to an unmediated discussion, in this unadorned space, the exchange quickly proceeds to Charlie’s blunt refusal to come to Los Angeles, to acknowledge his former promises to return to Los Angeles, or to concede his inconsistency in turning down a Geffen residency while accepting a Copenhagen residency. As soon as Charlie and Nicole enter this supposedly unmediated space, Charlie simply reiterates his career as the point through which their marriage must be mediated, revealing his inability to imagine the will of his wife and son as different from his own. As Nicole puts it, “you’re so merged with your own selfishness that you don’t recognise it any more,” resulting in his most violent gesture of the film – telling her that he has often wished she would die, as long as it didn’t affect Henry, or his relation with Henry. Charlie thus reveals that Nicole is really just a means to the father-son New York drama he has erected around himself and Henry – precisely the same drama Baumbach eulogized in The Meyerowitz Stories – making it totally unthinkable for Charlie that Henry might also prefer Los Angeles.

The violence of this moment marks the end of the film’s preference for blank backdrops, which are now taken in two directions. First, the stylised blankness of Charlie’s apartment is deflected into the starker and more austere marble and granite décor of the Los Angeles Family Court. Second, Charlie starts to decorate his apartment with plants and objects, as if unconsciously realising that he has been so determined to mediate his marriage through his own aspirations that he has confused those aspirations for the possibility of a genuinely unmediated exchange with Nicole. The film now enters a diffuse space in which Charlie doesn’t want to be married, but doesn’t quite want to be divorced either, instead searching for a way to conceptualise and aestheticise himself now that he will has been dissociated from the will of his wife and child. Whenever he encounters Nicole, he’s now hit with a slightly staged intensity that is nevertheless divorced from his own theatrical agency, producing long stretches where the two can’t quite make eye contact, forcing them to look awry at each other and displace their mutual gaze onto the space and fixtures around them.

It’s during this part of the film that Baumbach starts to inject more comedy into the tragicomic tone of the script, as the “unmediated” exchange between Nicole and Charlie exhausts all the gravitas and pathos that Charlie has tried to accrue by keeping the drama in New York, leaving a profound absurdity in its place – the absurdity of a husband and father who’s realised his wife and son have a will of their own, the absurdity of a New York intellectual set adrift in Los Angeles, and the absurdity of a self-styled theatrical auteur forced to grapple with a cinematic media ecology. All three of those tensions are part of the dynamism of Baumbach’s cinema as well, which is perhaps why all Baumbach’s cinematic gifts seem to converge on the brilliant scene – possibly the best in the film – in which Charlie’s relationship with Henry, and his role as a single father, is observed by an Expert Evaluator played by Martha Kelly, in the same deadpan observational mode she brings to Baskets. As if drawing upon the 80s slasher for one last burst of compensatory paternalism, Charlie brings a knife into the living room as a joke, before accidentally cutting himself, and leaving smears of abject blood on the whitewashed walls as he awkwardly shows the Evaluator out of the house. From there, he staggers between the sink and the towels before he collapses on the floor, watching Henry as he wanders in for a late night snack, oblivious.

Since the 80s, the slasher has been the figurative horizon for both the aspirations and the devolution of the American father, so seeing the slasher trope reduced to a study in absurd abandon marks the nadir of Charlie’s trajectory over the course of the film. It also changes the way in which the legal aspect of the film unfolds – especially the custody dispute, which boils down to whether Henry should be raised in New York or Los Angeles, and whether the Barbers are a New York or Los Angeles based family. Charlie’s biggest anxiety is that Henry will come to identify with Los Angeles, especially since his lawyers – first Jay, played by Ray Liotta, and then Bert, played by Alan Alda – advise him he has to reshape the divorce narrative to affirm them as a New York based family. This means that Charlie has to be in Los Angeles enough to establish himself as a responsible parent, but also maintain New York residency. In an older kind of film, this might be seen as a cynical and cruel approach from the lawyers – part of a bureaucratic system that is aligned against the man, and his desire for a genuinely unmediated exchange with his wife. Yet since Baumbach has punctured that fantasy of unmediated access so acutely, and revealed it to be just another iteration of a system that privileges the husband, the lawyers can’t play this antagonistic role in Marriage Story, let alone adopt the burden of articulating the husband’s more toxic marital impulses.

Instead, Charlie’s lawyers blandly reiterate his own agenda to him, and recommend that he do what he would probably do anyway, if he was thinking a bit more clearly. More generally, the divorce lawyers largely function as comic cameos, or comic relief – and it’s a real delight to see these three very different comic actors all riffing off another. Not only is the collegiality between the divorce lawyers comic in itself – they often pause their antagonistic delivery to enquire about each other’s families, and plan future social outings – but they break the trope of the antagonistic divorce lawyer in quite a comic way. Just when it seems like we’re going to be able to blame the lawyers for the whole messy situation, or deflect Charlie’s more antisocial impulses onto them, Dern, Liotta and Alda meld into a comic chorus that forces Charlie to shoulder the burden of his attitude towards married life, rather than relying on them to articulate his deepest, darkest assumptions about marriage.

In the end, then, Marriage Story is largely about Charlie trying to compel his family to return to New York because his gravitas as a father, husband and auteur don’t ramify in the same way in Los Angeles. While Baumbach seems attached, at times, to the trope of the aggrieved husband, he also knows enough about cinema to be prescient of the self-pitying and solipsistic lineage it springs from. Without New York present to automatically confer his genius, Charlie’s final goal is to affirm his genius, while also negating Nicole’s genius as an “intangible asset developed during the marriage.” Their two very different outlooks culminate with the final divorce settlement, which is marked by their two very different renditions of songs from Stephen Sondheim’s “Company.” The first, “You Could Drive a Person Crazy,” is delivered by Nicole in Los Angeles, at her niece’s birthday party, in a zany, comic, self-consciously childlike tone. The second, “Being Alive,” is delivered by Charlie in New York, to his theatre crowd, with an raw and naked sense of pain and wounded pride. While this rendition of “Being Alive” certainly exudes pathos and gravitas, it’s as an outdated, Broadway mode – as a period effect – and seems to relegate New York into the remote past, distant in time as well as space from the film’s bright Los Angeles backdrops.

An older kind of marriage film would have ended here, but Baumbach, like Sondheim, is prescient that this sincerity is just a bit too self-pitying as the final note of his vision. In fact, choosing not to end here is where Baumbach decisively severs the film from Charlie’s perspective, adopting a more sceptical distance as Charlie – belatedly – takes up a residency at UCLA to be close to Nicole and Henry. It’s too late for this gesture to seem noble – it’s just a necessity – especially since the family has largely moved on his absence, and Nicole is more discomfited than reassured to have Charlie and his dramas operating nearby. In the final moments of the film, Baumbach takes us through a series of beautiful tableaux of the family still operating, still contained in a single frame, but with Charlie now displaced as the main site of meaning and mediation. The last shot follows Charlie as he leaves Henry’s birthday party and walks down the street, as Baumbach zooms back and situates him in a Los Angeles milieu that is neither tragic nor uplifting, neither nurturing nor isolating. In the final instance, this is more a concession than a conclusion – a concession that walking is possible in Los Angeles, that living is possible in Los Angeles, and that the New York chamber dramas so important to Baumbach’s vision have been supplanted by a new world.

Love this analysis. Very well done.

Thank you – I’m glad it resonated!