Green: Halloween (2018)

Directed by David Gordon Green, and written by Green and Danny McBride, the latest addition to the Halloween franchise has managed to achieve what Friday the 13th, A Nightmare on Elm Street and The Omen have all tried and failed to achieve in the new millennium – a genuinely contemporary continuation of the original story, rather than a mere reboot or replication of earlier films. In this iteration of Halloween, the story has been retconned slightly so that Michael Myers is no longer Laurie Strode’s brother, but a random serial killer who just happened to target her and her friends on October 31, 1978. Forty years later, Laurie, still played by Jamie Lee Curtis, is living on a compound just out of Haddonfield, Illinois, and maintains fitful communication with her daughter Karen Nelson, played by Judy Greer, her granddaughter Allyson Nelson, played by Andy Matichak, and her son-in-law Ray Nelson, played by Toby Huss. Meanwhile, Michael Myers is still housed in high security lockup, and is on the verge of being removed to an even more secure prison for the rest of his life.

While Green may not recapitulate the story of the franchise in any great detail, the film does open with two quite different ways of thinking about Myers. On the one hand, Halloween raises the possibility that Myers can be understood in terms of psychology, and as a psychological subject – a position that is taken by a pair of true crime podcasters who turn up at Myers’ prison on the last day before he is transferred, hoping that this will give them one last chance to get an insight into his personality and subjectivity before he is cut off from all human contact for good. On the other hand, however, Myers is presented as non-psychological – as a blankness, an entity, a force, a shape – with one of the podcasters grudgingly admitting that “I’ve been following your case for years and I know nothing about you.” From the opening scene the film opts for this second way of seeing Myers, introducing him as an “awareness,” a spatial threshold and a mode of mediation, rather than a person or subject in any conventionally realist way. In a stunningly eerie scene, Green presents Myers alone, standing in a squared off-area, in the middle of a prison yard, positioned with his back to the podcasters, but nevertheless acutely aware of them, at least according to psychologist Ranbin Sartain, played by Haluk Bilginier, who has succeeded Donald Pleasance’s Dr. Loomis.

While he may be a psychologist, Sartain tends to espouse this same anti-psychological way of approaching Myers. In fact, precisely what makes Myers so fascinating to Sartain – as with Loomis – is that he seems to defy any psychological categorization or classification, instead existing on a plane that is outside of the human altogether, albeit not capable of being understood in supernatural terms either. For Sartain, Myers’ mask is the object that allows him to transmute this essentially inhuman identity in human form, and so the mask is the only object that traverses the threshold surrounding Myers in this opening scene, as one of the podcasters dangles it across the “no-go” line as a communicative conduit to Myers: “You feel it, don’t you Michael? You feel the mask.” While Myers may not respond directly, this mask-threshold unleashes an inhuman and unsettling energy that turns the whole prison yard awry, paving the way for a film in which Myers’ prescience and potentiality is more focused on his relation with his mask than in any film since the first. No surprise, then, that when the opening credits roll, they feature a smashed pumpkin face recovering its faciality, but also its anonymity, in reverse slow motion, prefiguring the experience of Myers himself in the film.

Correspondingly, Halloween offers two quite different ways of seeing Laurie Strode. On the one hand, the audience know her as a fighter and as a target for Myers over the course of forty years, and while everything but the original film might be elided from Green’s retcon, it’s inevitable that all the other iterations of Laurie play a part in Curtis’ presence here. Yet this is not at all how Laurie’s daughter sees her, since it emerges that Laurie’s effort to train and prepare Karen for her inevitable confrontation with Myers turned out to be a bit of a traumatic experience, and to estrange the two of them for many years. According to Karen, Laurie is a loose cannon who needs cognitive behavioural therapy, a position that seems to be tactitly shared by the podcasters, who try to convince Laurie that she and Michael need to have a sit-down – “let us help you free yourself” – to which she bluntly responds that “there’s nothing to learn – there are no new insights or discoveries.” More generally, Laurie seems reproached by suburbia as it stands in the film, which is presented as functional, well-balanced and well-regulated – in other words, a far cry from the kind of slasher histrionics that are still bound up her in her body and personality. Unlike virtually every other film in the franchise, Ray is a good father and provider, while we’re first introduced to Ray, Karen and Allyson on the verge of welcoming Allyson’s new boyfriend to the family, in an image of suburban continuity, and familial expansion, that is utterly alien to the rest of the franchise.

Finally, that all means that Green’s Halloween offers two ways of thinking about what Myers stands for. On the one hand, he is presented as a psychologically disturbed individual who belongs to an older time, and needs to be forgotten in order for Laurie, Karen and even Allyson to move on with their lives. Yet while that might be the consensus in the opening scenes, Green and McBride opt for the original depiction of Myers as a patriarchal inexorability, or inexorable patriarchal force, through which all suburban and family experience is mediated, even or especially when his presence and power seems to have waned. In the original films, Myers could never really be killed, since ideology – and especially such entrenched ideology – can’t simply be expunged, or disavowed. If anything, the films that come closes to killing Myers are Rob Zombie’s remakes, just because of how extensively they psychologise him, and so divest him of the inhuman and ideological force that made him impossible to kill in the first place. In that sense, Halloween plays as a bit of a reproof to Zombie, depsychologising Myers more than any film since the original, and revealing that, for all his grindhouse irreverence, Zombie’s sentimental psychologizing was quite a conservative gesture at heart, and in some ways complicit in the very things the franchise once critiqued.

Within that context, Laurie plays like a feminist derided by a post-feminist present, making for an incredible compelling character study and one of the very best performances of Curtis’ career. Time and again, Laurie is condescendingly told that she needs to get over her fears of this looming patriarchal and ideological force, or consigned to the realm of psychology, and reminded that her best bet now is to seek out medication and professional help. Watching her contend with these responses, I was reminded of Kate Millett’s comment that “patriarchy, reformed or unreformed, is patriarchy still: its worst abuses purged or foresworn, it might actually be more stable and secure than ever before.” It is that backdrop of reformed patriarchy that makes Halloween feel so attuned to the present moment – one in which the ideology of Myers could supposedly never return, only for precisely that complacency to make him more potent than ever when he does arrive. That produces quite an odd depiction of Haddonfield too, since while this neighbourhood feels more functional than at any other point in the series, this is also the first time that Halloween night seems to occur in mid-autumn, or even early winter, rather than the humid spring atmosphere of the other films.

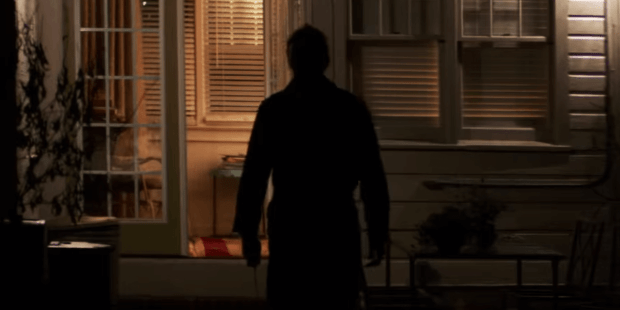

While Karen might accuse Laurie of relinquishing her family to fixate on Myers, then, Laurie knows that family can only exist if she contends with the forces for which Myers stands – forces that only she seems capable of testifying to in this putatively post-feminist present. Over the first part of the film, Laurie actually seeks out the positions that Myers once occupied, or where he might still show up, to the point where Green often shoots her in exactly the same way that Carpenter shot Myers in the original film, in a complex and sophisticated gesture of homage that reaffirms the continuity across the franchise more satisfactorily than a direct narrative sequel or total stylistic reboot could ever have done. More broadly, the psychological naturalism of Laurie and the other characters makes Myers blankness even more dramatic, while this could only be such an incredible character study of Laurie because of Myers’ rigorous blankness as well. Whereas Zombie opted for naturalism across the board, Green dissociates naturalism and blankness more than any other director – Carpenter included – to make a film gathers the greatness of every previous instalment but also works entirely on its own terms as a contemplation and condemnation of the present.

All those tendencies are intensified when Myers returns to this suburban matrix, in a process that takes two distinct forms. First, his prison transport bus is discovered, crashed, by a father and son who are on the verge of having a coming-out conversation, after the son anxiously discloses that he prefers dancing to football. The full disclosure never comes, however, as the father vanishes into the mist, and the son becomes Myers’ first victim. Secondly, Myers gravitates, as if by sheer awareness, to a petrol station where the two podcasters are refueling. While he works his way methodically through the other customers and attendants at the station, the focus of his first killing spree is still centred on these two individuals, who also form the first two deaths that we witness in any kind of grisly or visceral detail. In the contemporary world, no two spectacles encapsulate the promise and the threat of indefinite mediation quite like coming-out disclosures or true crime investigations – they’re both injunctions to further mediation – so seeing Myers dispose of these two demographics so brutally reinstates him as a point of mediation for ideological energies that both transcend and subtend the false transparency of a world that seems mediated in an amenable manner.

By containing and co-opting the mediatory potential of the digital world, Myers also becomes more mediatory than at any other point in the franchise, meaning that suburban space also becomes more porous and fluid than ever when mediated through his mask. In the first string of films, suburban normality was often mediated by Myers in quite baroque and flamboyant ways, but here it’s his fluidity that is most haunting, as if the supposed evacuation of toxic patriarchy from suburbia had allowed him to move more freely than ever before. As we shift from one astonishing shot, sequence and set piece to another, Myers becomes so mobile that he displaces the import of mobile devices, which do crop up, but are never quite the focus of attention, or capable of commanding and mediating the film as a whole. In the process, the film sinks further and further into the distended twilight that was so prominent in the first string of films as well – the continuous onset of a night that never fully arrives – reminding me of the indefinite twilit montage sequence that closes out Season of the Witch. Not surprisingly, that makes for a film that is every bit as suspenseful of the original, and even more ingenious, at times, in the way in which it pairs extensive dialogue and cross-cutting with what was essentially a silent and monofocal suspenseful style in Carpenter’s version.

As with Carpenter, this gorgeous crepuscularity quickly abstracts suburbia into so many reticulated interfaces of light and shade, in which Myers always feels like a subliminal presence in the background, or at the edge of the frame. The fact that I was continually scanning the background for his mask just made it scarier on those occasions when it did occur, as Green moves so fluidly – between long shots and close-ups, light and dark, from one awkward unstable vantage point to the next – that no juncture ever feels quite secure, or quite extricable from Myers’ looming presence, in what may be the best edited film in the entire franchise. Within that space, Myers’ movements grow so oblique – across fences, through backyards, between houses, from one open door to the next – that he can actually decelerate as the film proceeds, slowing to a walking pace as Laurie and her family retreat to her compound in the woods for the eerie final act, by which stage he is almost stationary.

Across this final act, what really ramifies is thus not much action, but the spectacle – iterated in a variety of different ways – of three generations of Strode women coming to terms with Myers’ inexorability, since it’s almost inevitable that Karen’s husband, as the well-balanced, well-meaning patriarch, should be the first target of Myers’ inhuman rage. Over the last couple of years, there’s been a movement in cinema and television towards interrogating the ways in which we sentimentalise white survivalism and assign it a profundity it doesn’t really possess, but no deconstruction has been so brutal and uncompromising as this final sequence of Halloween, which feels like a perfect coda to the franchise as a whole. In an inversion of everything white survivalism stands for, three generations of Strode women now find themselves becoming survivalists to stave off phallic monstrosity rather than perpetuate it, in a reminder that white women also have to survive whiteness when whiteness itself is defined in terms of suburban patriarchal authority. It feels apt, then, that this final showdown takes place as a series of iconographic images lit brighter than day by Laurie’s perimeter lights, suffusing the last moments of the film with a brighter-than-brightness – or whiter-than-whiteness – in which normality is finally intensified enough for Myers’ chalky mask to feel utterly naturalistic. From there, Green ends as abruptly and clinically as Carpenter ever did, leaving those final moments to linger like the dreams that occur just before waking, in one of the most brutal, suspenseful and beautifully executed horror manifestos of the last decade – true in all the right ways, and in all the best ways, to the utter uncompromise of Carpenter’s vision.

Leave a Reply