Allen: Manhattan (1979)

While they’re renowned for their sparkling dialogue and witty repartee, Woody Allen’s films don’t tend to be especially remarkable for their visual beauty. Manhattan is one of the few exceptions that proves that rule, however, since Allen’s collaboration with cinematographer Gordon Willis made this the most visually ravishing film of his entire career. Rather than open with his trademark white-on-black credits, Allen broke the mould here and started with an incredible montage sequence of Manhattan, scored to George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. As we move from one astonishing image to the next, Allen’s voiceover tries to come up with a opening sentence, and a story, commensurate to Manhattan. First he imagines it as a decline narrative, then a love story, then a sexual conquest, but derides each option for being too corny, too preacy, too angry. Finally, we realise he can only capture this city through the film that’s about to unfold, which promises to be the definitive celluloid New York experience.

Strangely, though, the emotional range of Manhattan is not so wide. Allen plays more or less the same character from Annie Hall, now rebranded as Isaac Davis, a self-loathing television writer who’s just embarked upon a relationship with seventeen-year old Tracy, played by Mariel Hemingway. Isaac has two divorces behind him, and his second ex-wife, Jill, played by Meryl Streep, is in the midst of writing a book about their relationship, after leaving him for another woman. Isaac’s main source of solace is his best friend Yale, played by Michael Murphy, but their closeness is quickly compromised when Isaac learns that Yale is having an affair with Mary, played by Diane Keaton, who he quickly falls in love with himself. This romantic ronde restricts the Manhattan that we see, embedding it in the city of Allen’s childhood, suffused with the last traces of the jazz age and the emergence of high Hollywood.

No surprise, then, that Manhattan is shot in sultry black-and-white, taking us through a series of still images that are forever burned into the cinematic consciousness. Allen’s neurotic insularity rarely lends itself to a genuine sense of grandeur, but Gordon Willis’ cinematography does wonders here. In many ways, the best parts of the film belong to Willis, whose New York vistas seem so detached from Allen’s story that they effectively work as a miniature city symphony on their own terms, not unlike Charles Strand’s Manhatta, released in 1921. That’s not to say that Willis doesn’t sync with Allen, but that there’s a strong sense of two different films unfolding here, producing the most beautiful images in Allen’s career outside of his more explicit pastiches of his favourite styles, directors and cinematic periods.

In particular, Willis draws stark distinctions between light and shadow, attuning every scene to the mystery of Manhattan at night. At the same time, Allen uses Willis’ cinematography to distance us from conversations to an unprecedented degree in his filmography – quite a bold move for a film that almost entirely subsists on conversation. His characters’ faces remain obscured for long stretches of the film, usually through darkness, but occasionally through brilliant patches of whiteness that are even more overwhelming, and that tend to drive the action even more propulsively – from the scene in a brilliantly lit gallery when Isaac first meets Mary, to the blinding racketball club where he first realises he wants to date her. In addition, Allen includes more driving scenes than any of his films before or since, in an effort to elasticise the action, while also intercutting the continuous conversations with still shots of the city, meaning we only see the people talking about half the time. Finally, Allen opts for angular compositions in which we only see one party in the conversation – typically by splitting the screen so that we have a speaker on one side, and a blank surface on the other.

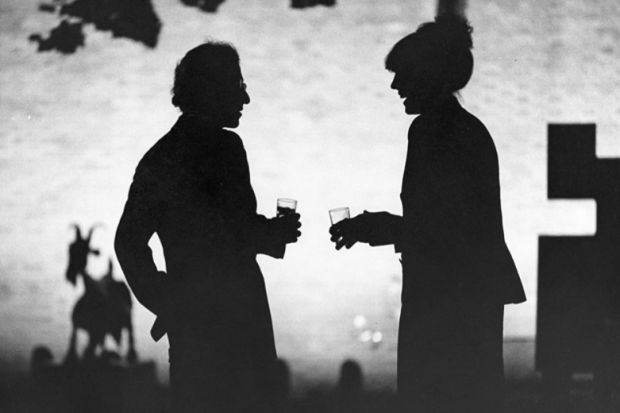

All of these innovations suggest that Allen is restless to exceed the conversational insularity of his previous films – not by discarding conversation, but by carving out a hush around the continuous conversation. Time and again, he seeks out space for the city to breathe around him, or at least tries to absorb his patter dialogue back into the rhythms of the city, which tend to swallow it most successfully when Willis opts for textural darkness or brightness. This all crystallises around the iconic scene in the Hayden Planetarium, which totally collapses Isaac and Mary into the silky textures of the film, as they emerge and recede from the darkness, set against planets and moons that are themselves abstracted to brilliant points of whiteness. This is the closest that Isaac and Mary come to a genuine romantic communion – and, time-wise, seems like their last great closeness before Mary’s mind drifts back to Yale.

In these gorgeous scenes, Manhattan is abstracted to a great cosmicity, with Isaac and Mary silhouetted against it, building a residual existentialism, a sense of speaking into the abyss, that offsets Allen’s normal conversational confidence. It feels quite natural, then, when his romantic escapades devolve into a full-on quandary about the meaning of life, as he finally lights upon the best story about Manhattan – a story about people who contrive ridiculous stories to avoid “the more unsolvable, terrifying problems about the universe.” At its very best, the cavernous spaces of the film, and the Planetarium, jettison Manhattan from our more sentimental associations, setting it against a cosmic void that is either flooded with noise or breathlessly still, apart from the occasional intrusions of the Great American Songbook. Yet this abstraction is also a way of blanking out the contemporaneity of the city, and situating Allen in a more timelessly revanchist New York, anchored in his own childhood.

Similarly, this modernist austerity also makes it harder to attach to much outside Allen’s own persona, unlike the more expansive and relaxed style of his later ensemble pieces, which allowed more scope for voices other than his own. Hence the central paradox of Manhattan – it’s Allen’s most beautiful film, but also the starkest in his self-presentation as an insecure pseudo-intellectual, cursed with a cultural inferiority complex that unleashes its anxieties on everyone and everything in its path. Time and again, the film lurches from the sublime to the ridiculous, as Allen’s responds to Willis’ gorgeous shots with a series of sophomoric discussions of art and philosophy. Allen has never been so overt as a mere name-dropper, and yet anyone who dares to be as intelligent as him, meet him on his own level, or simply engage with him (instead of being floored by his brilliance) is immediately pretentious. As a result, Manhattan veers vertiginously between Allen’s pretension and his need to pre-emptively police the projected pretension of anyone who might be more intelligent than him.

This is pretty silly – not everyone else in the world can be pretentious – but it takes on a more sinister edge when it contours Allen’s relation to women, since Manhattan is ultimately driven by two women who are considerably more accomplished than Isaac, both of whom are peremptorily put in their place. First we have Mary, Keaton’s character, who is introduced as a voice of cultural authority, meaning that Isaac has to immediately caricature her insights out of existence. While she uses terms that were quite common in art discourse at the time – otherness, negative capability – they provoke one of Allen’s most primal fears: specialist expertise. Time and again, throughout his career, Allen set his sights on academic, specialist of professional vocabulary, which is to say that he sets his sights on expertise itself, even as he came up with his own twee lexicon that he expected everyone else to fawn over. Yet it’s not just Mary’s expertise that threatens him here, but her taste – for all he bangs on about loving Renoir, Fields and Bergman, he can’t handle it when she takes him to a Dovzhenko film, and has to reduce her taste to an affectation at the very moment that it expands beyond his.

At the same time, Isaac never shows any real interest in Mary’s life, work, or art – he just offers her advice under the pretext of trying to make her better. For all her independence, or because of it, she’s painted as part of the same pattern of intellectual servitude that Allen attaches to women throughout his career as well, since she married her university professor, and is attracted, despite everything, to Isaac’s continuous sophomoric pronouncements. She’s always talking about how much she has to offer, but the broadest horizon that she (and the film) can imagine for her is very telling: “I could sleep with the entire faculty of MIT if I wanted to.” Beyond a certain point, this invalidates her claim to be a feminist, or even a genuinely free-thinking woman, since her ideologies are so over-egged, and so indebted to her sexual fetish for academics, that she feels indoctrinated rather than informed or inspired.

This is even more the case with Jill, referred to as the most “immoral, promiscuous, psychotic” of Isaac’s pair of ex-wives. Interestingly, Streep has the strongest presence in the film – she’s the only actor who really escapes the force field of Allen’s narcissism, a testament to her staying power even at this early stage in her career. Likewise her character, Jill, is the only woman who genuinely resists Isaac, and yet even this resistance is framed as a form of fixation, obsessive enough for her to write an entire book about their relationship. The sheer act of resisting Isaac has also apparently sufficed to turn Jill into a lesbian, which also means that she can’t really be understood as a woman who has resisted Isaac, since to be a woman in Manhattan means to be seduced by Isaac’s nattering. For all that Jill is “punishing” him by being a lesbian, Allen is punishing the character by making her a lesbian (since, for him, lesbianism ultimately is a punishment), while his terror of her tell-all feels creepingly prescient of the present moment too, when Ronan and Dylan Farrow’s claims have become so visible.

Isaac’s relation with both these women is concisely encapsulated in a conversation he has with Mary at the peak of the Planetarium scene – the conversation that explains why he can never follow through on the breathless romanticism of this scene. As soon as Mary asks him to play a game about facts he doesn’t know (planetary satellites), he explains to her that rational thought is overrated, before chastising her for relying too much on her feelings a moment later. It’s an impossible demand – don’t rely on rationality for knowledge, but don’t rely on feeling either – that Isaac resolve through the most repulsive image in the whole film.

As Willis’ inky darkness folds Isaac and Mary into a single figure, Isaac tells her that “nothing worth knowing can be understood with the mind. Everything really valuable has to enter you through a different opening, if you’ll forgive the disgusting imagery.” For Allen, knowledge is inextricably gendered, something women can only achieve through sexual intercourse with a man, just as his hatred of real expertise is ultimately a threat to his libidinal prowess. As this Planetarium scene makes clear, nobody is allowed out of his orbit – literally – since intellectual achievement here is nothing more nor less than crude sexual dominance. No surpise, then, that when he lists the things that make life worth living, he comes up with a bevy of basic classics by men, but can only acknowledge the existence of women by way of “Tracy’s face.”

Just as Isaac’s inability to fully concede the existence of women takes place via the two adult woman in the film, so he’s forced to deflect his need for sexual satisfaction onto two deeply dysfunctional relationships within the film. The first is with the island of Manhattan itself, which he can claim as his own in a way that he could never claim an actual woman. We see this just after the Planetarium scene, when Isaac’s failure to commune with Mary propels Allen into the most beautiful shot he ever took of the city – a languorous tracking-shot of his taxi as it curves into FDR Drive, skyscrapers sparkling mysteriously in the background. Yet this is ultimately a pretty basic vision of Manhattan, taking in the most touristy sites, from the Brooklyn Bridge to a horse-and-buggy ride in Central Park, so generic at times that neither the sites nor the images even feel like Allen’s anymore – especially the establishing-shots, which seem directed, or at least orchestrated by Willis. You can’t help but think of directors like Scorsese, Friedkin, Lumet, or Coppola, whose films from this era were every bit as embedded in the city, but who didn’t have to claim Manhattan as their own precious thing.

The second dysfunctional relationship in Manhattan occurs between Allen and Tracy, his seventeen-year old protégé, so it’s no coincidence that he spends a great deal of their time together explaining New York to her, despite the fact that she seems to have lived there all her life. Unable to concede the existence of women who have even the remotest possibility of being his intellectual equal, Allen discovers his true type here – younger women he can talk down to. As much as Isaac wrings his hands about the age gap between himself and Tracy, this age gap is the main thing drawing him to her, since it guarantees a disparity of life experience that can withstand the possibility of even her also being his intellectual equal, which she indeed turns out to be. So paranoid is Isaac that even a woman twenty years younger is an intellectual threat, so even Tracy doesn’t present as a real partner, but an even more extreme projection of his terrors of being intellectualy outranked by women generally.

As a result, Isaac doesn’t even really participate in his relationship with Tracy, and refuses to take her on her own terms, instead mocking her, talking down to her, and assuring her that she can’t be in love with him (or even know what love is), even as he postpones breaking it off with her for good. Beyond a certain point, the relationship is simply him berating her for dating him – the appeal lies in telling her she’s getting too hung up on him, or explaining to her why she hasn’t fallen in love with him (or why she can’t fall in love with him). Yet Isaac’s main gripe with Tracy isn’t that she’s too naïve, but that she’s too serious, too worldly, too earnest – in a word, too mature, giving you the uneasy suspicion that he’d prefer a woman much younger, or at least a woman prepared to infantilise herself in a far more overt manner.

In short, Isaac uses self-deprecation as a way of reiterating the power imbalance with Tracy – and this should make us wary of putting too much stock in how thoroughly the film articulates Allen’s own pathologies as well. No doubt, this is one of Allen’s best directed films, incredibly poised in its structure, and remarkably deft in the concision and precision with which Allen contemplates his own limitations. Yet this self-deprecation is finally just another form of narcissism, an injunction to Isaac’s friends, and Allen’s audiences, to remind him how great he is. Throughout his career, Allen constantly harps on about how screwed up therapists are, but Manhattan makes it clear as never before that this is a smoke screen – a way of deflecting his own pathological use of therapeutic care to exert power of women, as well as a strategy for belittling the expertise that his female love interests acknowledge in their own therapists.

For all that he bangs on about his inadequacies, then, Allen is always presented here as a Casanova in the sheets, and that machismo is what comes through most in Manhattan, a celebration of Allen in the role of predator, a macho prick in a nerd’s body, and all the more dangerous for that. The cinematic cues are all on point, right down to the closing nod to City Lights, but Allen is no descendant of Charlie Chaplin here – he’s “Theodore Reich with a touch of Charles Manson,” in one of the most beautiful, and unwatchable, films in his whole career.

Leave a Reply